For years, companies could load up on debt and use the interest to shrink their taxes. Lawmakers wanted a clear, objective speed limit so the deduction stays tied to real earnings not clever structuring. Today’s rules do exactly that. They mostly affect (1) large, highly leveraged corporations and (2) partnerships when losses flow to limited partners.

Yesterday vs. Today (What Changed)

Before 2018:

The U.S. policed “thin capitalization” with debt-to-equity tests. If your company was “too much debt, not enough equity,” some interest got denied. It was narrow, fussy, and easy to plan around.

Since 2018 (the modern system):

There’s now one main rule: an earnings-based cap. Each year, your business can deduct interest only up to a slice of your earnings (defined in the tax code). It’s straightforward and applies broadly.

A 2025+ tweak that matters:

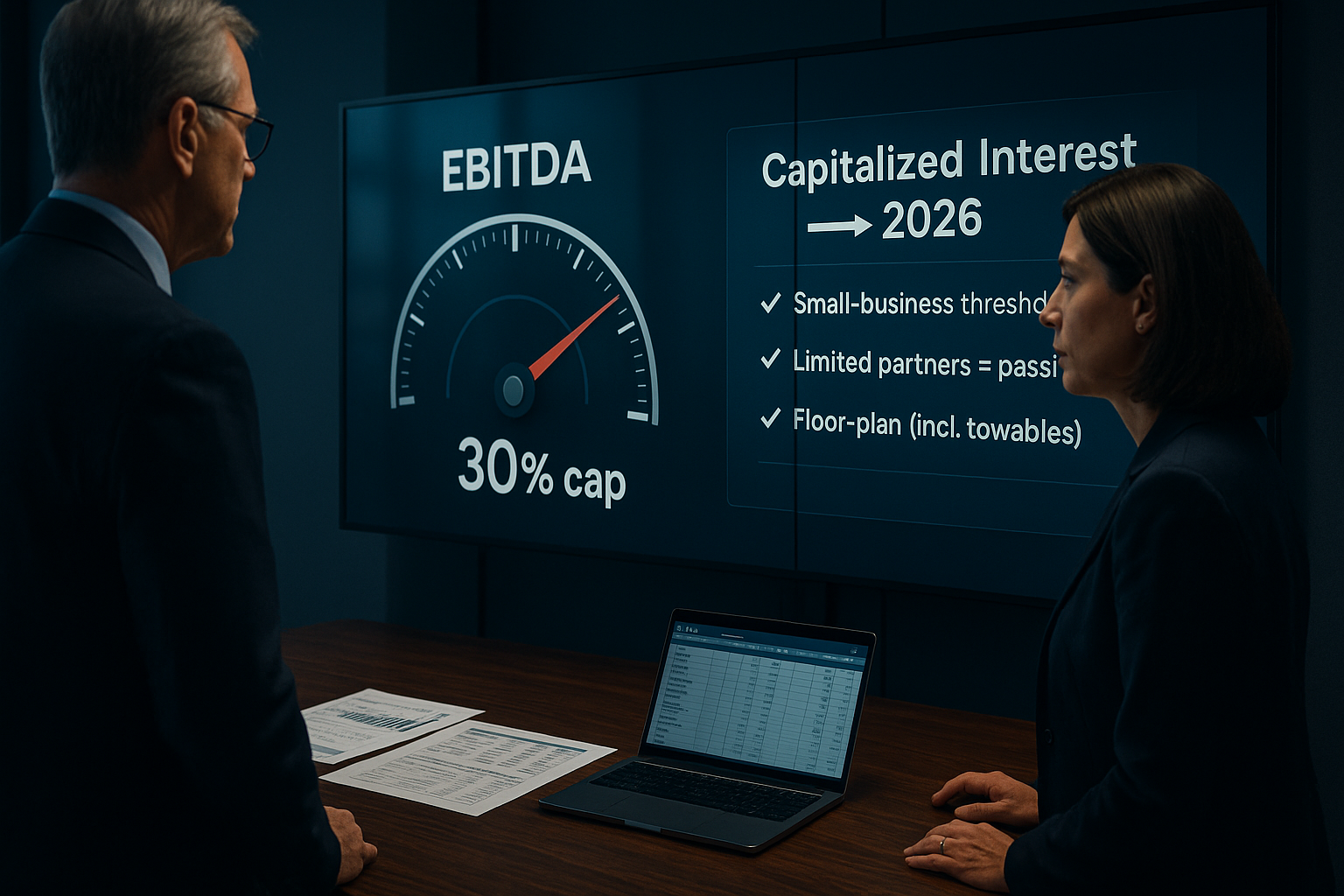

Starting with tax years after 2025, the cap continues to be measured against EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). That usually means a larger deduction than in 2022–2024.

But there’s more:

- The definition of Adjusted Taxable Income (ATI) is expanding. From 2026 on, ATI must also include certain international tax items like Subpart F income, GILTI, and Section 78 gross-ups, along with related deductions under 245A and 250. This generally boosts ATI and lets multinationals deduct more interest.

- New rules also clarify how the cap interacts with capitalized interest (interest rolled into the cost of assets). The limitation applies whether interest is deducted directly or capitalized. Allowed amounts are applied to capitalized interest first, and any disallowed interest carried forward won’t be forced back into capitalization rules again.

Who Feels It Most?

1) Large, leveraged corporations

If your interest costs are big compared with your earnings, the cap can bite. You don’t lose the deduction forever—excess interest generally carries forward—but you may not get it all this year. The new coordination rules also make sure you can’t sidestep the cap by pushing interest into asset costs.

2) Partnerships that send losses to limited partners

Even if the partnership isn’t capped, limited partners often can’t use those losses right away because of the passive-loss rule. Here’s the key line from the law:

“Except as provided in regulations, a limited partner shall not be treated as materially participating in the activity.” — IRC §469(h)(2)

Plain English: losses (including interest-driven ones) allocated to limited partners are typically passive. Passive losses can’t offset your salary or other “active” income; they sit and wait until you have passive income or you exit the investment.

The Other Moving Parts (Without the Jargon)

Small-business relief:

If your average annual receipts are at or below the inflation-adjusted §448(c) threshold—$29,000,000 for tax years beginning in 2023; $30,000,000 for 2024; and $31,000,000 for 2025—the big interest cap generally doesn’t apply (uses a three-year average and excludes “tax shelters”).

Special industry choices:

- Some real-estate or farming businesses can opt out of the cap, but they give up faster depreciation in exchange.

- Dealers with “floor-plan” inventory financing (e.g., autos, now certain towable RVs/campers) can often deduct that interest in full—but again, there can be trade-offs with depreciation.

Cross-border guardrails for very large multinationals: Extra rules (including the BEAT provisions) can reduce the benefit of interest paid to foreign affiliates.

How It Works in Practice (Think: Gates You Pass Through)

Are you small enough to be exempt? If yes, you’re done.

If not, apply the earnings cap. From 2026 on, it’s measured against EBITDA plus certain international inclusions. Anything above the cap gets carried forward.

If you’re a limited partner, check the passive-loss rule. Even allowed losses may be stuck until you have passive income.

Consider special elections/exceptions and their trade-offs. Sometimes you can sidestep the cap, but you may have to accept slower write-offs elsewhere.

Capitalized interest counts too. The cap applies whether interest is deducted or rolled into assets, with allowed amounts applied to capitalized interest first.

Two Quick Examples

Big manufacturer with lots of debt:

Strong profits, but heavy interest. The earnings cap allows most—maybe not all—interest this year. The rest carries forward. If some interest must be capitalized into assets, the cap still applies first to that portion.

Real-estate fund with limited partners:

The fund passes a large (interest-heavy) loss to investors. The fund itself might not be capped, but limited partners likely can’t use the loss now because it’s passive under the rule quoted above.

The Bottom Line

The modern approach is objective: a clear speed limit that ties the interest deduction to earnings. Beginning in 2026, the base for measuring the cap will be a bit broader (including certain international tax items) and coordinated with capitalization rules. The shift mainly affects big, leveraged companies and partnership structures where limited partners receive losses they can’t currently use. It doesn’t punish borrowing; it just keeps deductions in step with real, recurring profits.

We welcome your feedback, questions and ideas, comment below or email us at info@ifindtaxpro.com.

Interested in crypto accounting? Try Minutes Crypto — Digital-Asset Ledger & Tax Suite to streamline your workflow → minutescrypto.com